The most analyzed positions in the open games (1. e4 e5) must be the ones in the mainline Ruy Lopez, which as such, is not in my repertoire. But many other double-king-pawn middlegames commonly arise, that are not part of the Ruy Lopez. Although most are not considered as critical at high level, they share a lot of similarities to our Ruy. Of course, there are too many to name, and too many for most players to analyze in detail, so many of them are played on some basic principles that most players develop as they play these positions often enough. Sometimes, it’s more complicated than that, but in a recent game I played against an up-and-coming junior (rated about 2150), it was enough for a crushing win in what looked to be a long, closed game.

Before going over that game, I would be remiss to omit the continuation of, well, the namesake of my last two posts. During my recent trek to Berkeley (in which I was wise enough to stay overnight instead of driving an extra 100 miles…), I scored one win and one loss in my first two games, being borderline lost in the first and crushing from the beginning in the second. Although it might appear that I played like a normal human being this time, and lost the first but won the second, a read of my last two posts will suggest (correctly) that I won the first, against an expert, and lost the second, against a very tricky Grandmaster Enrico Sevillano. When I sort those out in my studies of chess psychology, I will revisit those, perhaps in a later post! But for now, it’s double king pawn games.

Li (2225) – Vidyarthi (2153), Berkeley October FIDE

1. e4 e5 2. Bc4 Nf6 3. d3 Bc5 4. Nc3 c6

Although White’s move order is intended to spring f2-f4, when Black is able to counter with …d5, we usually revert back to usual double-king-pawn play. Black can settle for …d6 anyway (as in the game) or strike out with …d5.

5. Nf3 b5 6. Bb3 d6 7. Ne2

This is a plan that should be familiar to most players of these and similar lines; White getting ready to reroute a knight to g3 and hopefully f5.

7…O-O 8. Ng3 h6?!

This is already a step in the wrong direction, as …h6 is rarely helpful to Black in the long run (especially after castling, when it is just a target), Understandably, Black does not want to be bothered by Bg5, but with a knight on g3 I probably wouldn’t have bothered, as after …h6 the bishop cannot keep the pin.

Of course, we are still far from the dream scenario, but if white gets to post a knight on f5, Black is going to be a bit uncomfortable, as trying to kick the knight with …g6 will hang the h6-pawn in most lines.

9. O-O Be6 10. c3

About as reasonable a decision as any; White’s bishop is powerful, but usually can’t stay on the diagonal for long. I don’t have too much experience in these types of games, but it seems that when Black blunts the a2-g8 diagonal, it’s time to switch gears and train sights on f5 and beyond. 10. Bxe6 fxe6 in particular did not seem helpful.

It’s a good time to take stock in what both players may want. I obviously wanted a knight on f5, but trying to have both knights trained on f5 is hard (Nh4 gets squashed by Nxe4 discovered attack, for now). Regardless, from that perspective it’s important to keep the pawn on e4.

Black is clearly helped by the pawn on e5, but supporting it will become a bit of a challenge if he tries to break in the center with …d5 (which I believe he should have tried). Most importantly, it’s important to keep notice of White’s possibilities on the kingside.

10…Nbd7 11. a4 a6 12. h3

Possibly not necessary, but seemed like a good way to improve my position before taking any action. 12. h3 in particular was based on the possibility of Black trading off a pair of minor pieces on the kingside; for example, otherwise 12…Bg4 13. h3 Nh5! (and if hxg4, Nxg3!). Note that h3 is not a target in the way that h6 is for Black.

12…Bb6 13. Bc2 Qc7?

When I saw this move, I was a bit confused as it didn’t seem to jive with 12…Bb6. I suspect Black just wanted to keep the bishop away from d3-d4 and finish development, but “developing” Black’s queen is not a huge deal at the moment, and if he wanted to, 13…Qe7 was a much better option, preventing 14. Nh4.

I’m not really sure what I would have done. Nf5 intending to answer Bxf5 with exf5 is not the end of the world, but that needs to be prepared reasonably well as Black takes a lot of the center after that with …d5. Now White is guaranteed a knight on f5, with a fairly substantial advantage.

14. Nh4 Rfd8 15. Ngf5

Now things are starting to get scary for Black, as White is poised to follow with Qf3, Qg3 etc. There are many threats after Qf3, so determining the best response takes a bit of thinking. 15…Kh8 seems relatively best, when the hasty 16. Qf3 d5 (e.g.) 17. Qg3 runs into 17…Nh5 followed by the surprising 18…Ndf6!.

15…Nf8? 16. Qf3

Perhaps Black intended to move his king but missed that White is also threatening 17. Nxh6.

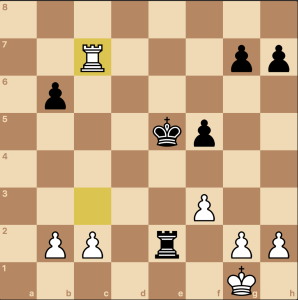

16…Bxf5 17. Nxf5 N6h7 18. Qg3

Because of the dual threats of Nxh6+ and Qxg7#, Black is kind of toast already. The only try is to block the g-file, but Black is not coordinated enough to deal with White’s counters to that.

18…Ng6 19. h4 Nf6 20. Bd1 h5 21. Bg5

Black had only one way to stop h4-h5, but White again threatens Bxf6 and Bxh5, winning probably much more than just a pawn. Black’s pieces are all helpless to protect the kingside.

21…Kh7 22. Qf3

Trying to beef up the attack; Black did not oblige and sacrificed the exchange with 22…Ng4 but White’s attack kept up and I was able to win the rest without significant trouble.

Despite a fairly even-handed opening, the rest was pretty much on common open game principles. Black would have done well to keep in mind White’s mechanisms for activating that h4-knight and preparing active counterplay such as …d7-d5.

Stay tuned for next month’s post, which will feature some games from the upcoming Bay Area Emory Tate Memorial!