Hi everyone, I’m US Candidate Master Daniel Johnston and this post is about coming from behind in lost positions. First let me say that I’ve been following Chess^Summit with interest since my coach, GM Eugene Perelshteyn, told me about it (Eugene is also Isaac’s coach!), so I’m happy to be a guest here today.

We all know the reason why chess is such an unforgiving game: If you make a mistake, it can give your opponent such a big advantage that coming back can be close to impossible. Through tournament practice, however, I’ve learned that seemingly sure defeats can turn into draws and wins, even against strong and highly experienced opposition!

A lot of times players may not be aware of how possible it really is to come back from an objectively hopeless or nearly hopeless position. In the past when I would get a bad position against a strong opponent I would view it as torture. Not anymore, however, now that I know any position can turn into a win.

Yes, I (yellow shirt), did come from behind to draw this game!

So what strategies will enable you to escape defeat? Here are some I’ve noticed that seem to work well and increase your chances of pulling off a comeback 🙂 Also check out IM Alex Katz’s article specifically about swindles.

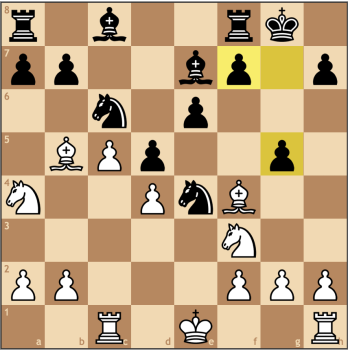

First, you have to be aware that regardless of rating or title, any player can blunder. Let me show you an example from last year’s World Open, when I was playing against IM Timothy Taylor. This game made me start to understand that any player can make big mistakes at any time.

At the time of the game, I couldn’t believe what had just happened. I was elated to have beaten an IM, obviously, but didn’t think winning after a series of poor moves from my opponent was that impressive. True, it may not be. But this kind of thing happens far more often at a far higher level than many people may realize. While I was shocked then that an IM had played this way, now I think it would only give me a mild surprise.

The first mistake in this game, taking on g7, should actually not be that big of a surprise. Imagine the thought process, “Ok, now I’m going to take on g7, removing a defender, and then check on d4, making him weaken his kingside.” Missing that this actually helps black can easily happen. And it’s true that even there, white has a serious advantage. Many strong players would go for that just like my opponent did. Note on the flip side that as the player that has the advantage it’s important to be careful and make sure that the line you’re choosing puts the maximum amount of pressure on your opponent.

The other mistakes in this game are more difficult to understand, and usually wouldn’t happen from a titled player. However, anyone can have a bad day and taking advantage of these situations is very important. I’ve seen many players blow wins or draws against higher rated opposition by being too cautious or trusting their opponent too much. Higher rated players already have a skill advantage, and giving them this further psychological advantage can be deadly. Instead, it’s important to be objective about both you and your opponent’s skills, but you should also realize that you have a fighting chance against anyone and shouldn’t be intimidated. This often comes simply by getting practice against strong players, like I got in this game.

While it’s important to take advantage of the kind of mistakes that we saw in this game, the truth is that higher rated players blunder a lot less frequently than lower rated players. Counting on them to simply make an outright blunder is typically not going to be a very fruitful strategy (but you also must be aware that them blundering is always a possibility). One useful thing to keep in mind, however, is that if even FIDE titled players make these kinds of mistakes, what about national masters and experts? The truth is that there are often tons of mistakes from both sides in my games against these players, and bad positions turn around quite often, so you shouldn’t lose heart against them unless your position is truly disastrous!

While higher rated players may not blunder much, they are still very susceptible to making mistakes (like Bxg7 in the above game). In order to increase the possibility of any opponent making a mistake, you need to try and put as much pressure on them as possible when you are in a bad position. Imagine that you’re in a complete positional bind against a strong player. If you simply wait and do nothing, the game is most likely already over. Your experienced opponent will probably easily exploit their advantage. To get yourself back into the game, therefore, it’s imperative to create dynamic counterplay.

If you’re unaware, chess can be divided into statics and dynamics. Statics are long-term things that aren’t going to change easily, like pawn structure or material. Dynamics, on the other hand, are short term aspects of a position, such as king safety or piece activity (although activity could also be considered a static advantage if you have, for example, an outpost or two bishops).

If your opponent has a static advantage, you have to counter by creating dynamic counterplay. This isn’t just true when you’re massively behind; it’s true in every situation. After all, if your opponent has a long term edge and there’s nothing you can do about it, your only choice is to try to utilize short term advantages to try and change the nature of the position.

Changing the nature of the position is almost always favorable when you’re behind. In a dynamic position, your opponent at the very least has to shut down your counterplay. And nobody likes being under pressure. If you’re getting squeezed to death, the odds of your opponent making a mistake and letting you back into the game may be slim. But if you give him problems to solve, even if it’s objectively still good for him, you’re giving yourself a chance.

Here’s a game I played at this year’s World Open against FM Dov Gorman, where he executed this to great success against me.

So did my opponent make the right decision by sacrificing a piece? Despite my loss, and the shots he could’ve played with Rxf2, I’m inclined to think not in this case. After all, had I managed to keep my head better and calculated more accurately, I would’ve been on my way to victory. Maybe my opponent could’ve looked for some other kind of counterplay later. It’s crucial to not just complicate hastily, but in a way that can be supported by the position as much as possible. I think the line here is something you learn as you become a better chess player.

Either way, this is a good example of the kind of dynamic counterplay and pressure I’m talking about. When faced with only a small positional deficit, my opponent went all in to change the nature of the position! You should be searching for such opportunities if you’re statically behind.

Exactly what kind of dynamic position do you want? I think a good general strategy is to force your opponent to do concrete calculations. This is what Dov Gorman successfully did against me. While some players may of course be very good at calculation, this is an area where anyone can make a mistake, and where a mistake can be game-altering. Calculation is simply an additional avenue to outplay your opponent, thus giving you more chances, which is true even if your opponent is better at calculation than you are. Players are also often especially hesitant to go for things that look messy when they have a big advantage.

A calculation error in a complex position can easily change the evaluation dramatically. So while any kind of dynamic position is good when you’re at a disadvantage, I think the best is one where your opponent is forced to do serious calculation. Note however that this may backfire if your opponent is a skilled calculator, so as I said before, try and create complications in the way most supported by the position.

Also, keeping your head after you make a mistake and continuing to play as usual is one of the best things you can do. Those of you who play bullet will know that a lost position is hardly something to panic over, especially if you’re up on time. After all, anything can happen. While classical chess is of course not so wild, anything can still happen, and the way bullet players continue to fight on unconcerned by deficits is a good example of the kind of attitude to take during long games.

Actually, a lot of the time, your position may not even be as bad as you think. Here’s an example of a game I played against a strong 2100 where I blundered a pawn on the seventh move but won anyway.

As you saw from the game, I got a lot of play for the pawn, even though I lost it completely by accident. Ok, so I got lucky there that my position was not actually so bad. But I did the right thing by staying calm. Instead of letting a mistake or bad position get you down, you should focus on using the resources you do have in the position. After all, your opponent is not a computer so it’s more than likely you’ll have some chances. Also, I was able to play quickly and put my opponent in serious time pressure, which always increases your chances greatly.

To sum up, coming back from a bad or lost position largely comes down to being aware any opponent can make a mistake, changing the nature of the position by creating dynamic counterplay (if you can force your opponent to calculate, that’s even better), and staying calm and focusing on using the resources in your position. Executing this in games, of course, is far less simple than it sounds. It is largely based on your skill as a player to recognize chances and correctly decide what kind of counterplay you should go for in a given position.

Also, I should note that all of the above becomes more and more effective as the tournament progresses to the later rounds! Here’s an example of a mistake-laden game I had in the last round of the 2015 World Open against NM Sahil Sinha, of Chess Rival ^ Summit fame. Sahil’s claim of beating Chess^Summit writers is at least true in my case, as he’s won the other two games we’ve played.

Everything we said about complicating the position and forcing your opponent to calculate proved true in this game. Even though I played quite poorly, by latching onto the counterplay I did have I was able to survive a completely lost position. I think chances are good, however, that Sahil would’ve won this game had it been played in the early rounds of the tournament. Of course, any tournament player will be aware of the proliferation of mistakes in the concluding rounds of the tournament. That means you should dedicate even more of your energy to searching for counter chances towards the end of a tournament, because they are much more likely to be there.

I think coming back from a bad position is almost an art form in itself. So if you find yourself in trouble, try not to be disheartened. This is simply a natural part of the game of chess, and as good an opportunity as any to do your best and show off your skill! Of course, your opponent may play great and rebuff all your attempts at counterplay. Or you may have truly messed up your position beyond any repair.

But the more tournaments I go to, the more it seems to me that chess players make their own luck. I never cease to be astonished by the turnarounds I see at the top tables of every tournament. Maybe a comeback of yours will be one of those to blow me away 🙂

Over the summer this year, the 35th US Chess School occupied the famous San Francisco Mechanic’s Institute, the oldest running chess club in the U.S. I had been invited again and I was looking forward to another great chess camp. The camp’s full schedule started at 10:00am and ended at 6:00pm that last 4 days. Each day consisted small breaks and an hour long lunch break. The chess camp consisted of 11 strong players from California, and one strong WFM from Texas. The 12 attendees were: FM Rayan Taghizadeh (2336), (almost FM) Josiah Stearman (2315), NM Siddharth Banik (2309), NM Ladia Jirasek (2305), WIM Agata Bykovtsev (2297), WIM Annie Wang (2251), NM Alex Costello (2247), WFM Emily Nguyen (2241) from Texas, Balaji Daggupati (2108), Cristopher Yoo (2089), Seaver Dahlgren (2079), and Karthik Padmanabhan (2035). Our coach was the well-known International Master Greg Shahade, founder and president of the U.S. Chess School, founder of the New York Masters and the U.S. Chess League, and who is also a pretty good poker player. This year Greg had no help but was ready to go 1 against 12 and leave no chess stone unturned.

Over the summer this year, the 35th US Chess School occupied the famous San Francisco Mechanic’s Institute, the oldest running chess club in the U.S. I had been invited again and I was looking forward to another great chess camp. The camp’s full schedule started at 10:00am and ended at 6:00pm that last 4 days. Each day consisted small breaks and an hour long lunch break. The chess camp consisted of 11 strong players from California, and one strong WFM from Texas. The 12 attendees were: FM Rayan Taghizadeh (2336), (almost FM) Josiah Stearman (2315), NM Siddharth Banik (2309), NM Ladia Jirasek (2305), WIM Agata Bykovtsev (2297), WIM Annie Wang (2251), NM Alex Costello (2247), WFM Emily Nguyen (2241) from Texas, Balaji Daggupati (2108), Cristopher Yoo (2089), Seaver Dahlgren (2079), and Karthik Padmanabhan (2035). Our coach was the well-known International Master Greg Shahade, founder and president of the U.S. Chess School, founder of the New York Masters and the U.S. Chess League, and who is also a pretty good poker player. This year Greg had no help but was ready to go 1 against 12 and leave no chess stone unturned.