In some openings, a player may play h3/h6 to prevent the bishop from pinning a knight to the queen. For many openings, this is standard, but once that player castles on the kingside, h3 becomes a target. When I coach any chess player, I make sure he knows to avoid moving pawns in front of their castled king, because it begs for trouble (except for fianchettoing of course). Don’t believe me? Here is some proof of some botched kingside pawn structures:

Wang – Steincamp (Virginia Open, 2012)

1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 a6 6. Be3 e5

7. Nf3 This is not typical, main line is 7. Nb3. This gives white the option to play f2–f3 and g2–g4 to attack the kingside.

7…Be7 Because my opponent has deviated from book, 7… Be6 is a positional mistake because 8. Ng5 results in either a loss of a tempo or the loss of the bishop pair.

8. Bc4! Good move, my opponent immediately takes control of the g8–a2 diagonal, making it difficult for me to develop my bishop.

8…Nc6

9. h3 This move is strong as long as white castles queenside. The idea is obviously to eliminate …Bg4, so I can’t say this is a mistake.

9…O-O

10. O-O? A strategic mistake, as now h3 is a target for my poor light squared bishop. 10. Qd2 would have been an interesting try for white.

10…Bd7 11. Nd5 Nxd5 12. Bxd5

12…Qc8 Without any hesitation, I immediately created a battery to attack h3. I’m not threatening to take yet, but I’m planning …Kh8, …f7–f5, and potentially a rook lift.

13. h4?? My opponent flinches. There was no need to try this yet, 13. Qd2 would have been interesting.

13…Bg4 14. Bg5 Bxg5 15. hxg5

15…Nd4 Right now, my game plan is just to ruin my opponent’s kingside. Forcing him to move pawns in front of his king will win me this game.

16. Qd3 Bxf3 17. gxf3 Qh3!! 18. Bxb7 Rab8 19. Bxa6 Nxf3+ 20. Qxf3

20…Qxf3 –+ The game continued for a few more moves before I found checkmate. 0-1

While my opponent helped my attack, I was able to win because he created holes in front of his king. What many players don’t understand about playing h2–h3 in front of the castled king is that it creates 2 targets, the h3 pawn AND the h2 square.

This next game I played against a much stronger opponent, and while I should have lost, a weak kingside gave me a thematic tactical resource.

Katz – Steincamp (Maryland Open, 2012)

1. Nf3 c5 2. c4 Nc6 3. b3 g6 4. Bb2 Nf6 5. e3 Bg7 6. d4 cxd4 7. Nxd4 O-O 8. g3 Nxd4 9. Qxd4

9…Nh5?! Not necessary at all. If I were to play this position now, I would opt for 9… d7–d5, taking advantage of the undeveloped b1 knight.

10. Qd2 Bxb2 11. Qxb2 d5 12. Qc3 dxc4 13. Bxc4 Bg4 14. Nd2 Rc8 15. Qb4

15…a5 This move shows that I was worried about Bxf7+ with the discovered threat on the g4 bishop. What I didn’t see was 15… b6 16. Bxf7+ Rxf7 17. Qxg4 Rxf2!! and if White tries to take the rook, Qxd2+ followed by Qxe3 will blow open the position in my favor decisively.

16. Bxf7+ Rxf7 17. Qxg4 Rc2 18. Qd4 Qc8

19. O-O Here we go. White has a weakness on the kingside because he doesn’t have a light squared bishop. As of right now, White has weakness on f3, h3, and g2.

19…e5?! Not necessary. The idea is to remove the defender on the knight. One key idea I heard a few years later was to not try silly tactics on your opponent. This move weakens me more than my opponent.

20. Qd6 Qf5 21. e4

21…Qh3 Not threatening anything yet. 22. Rfc1 should solve any problems, but like last game, pressure on a weak king results in passive play, and passive play leads to blunders!

22. Qd3?? Nf4!! 0-1 My opponent resigns on the spot, the knight controls all of the weak squares in white’s kingside. Meanwhile white cannot take the knight or the rook.

This game was very scrappy, and frankly I played subpar, but that being said, recognizing the weaknesses on the kingside won me this game.

The next (and final) game, is probably the most strategic of the three. I personally believe that this is one of the best games I’ve played in my career.

Steincamp – Chrisney (Eastern Open, 2013)

1. c4 Nf6 2. d4 e6 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. a3 Bxc3+

5. bxc3 This is not my line of choice, but I knew how my opponent would respond, so for the most part, this is preparation.

5…O-O 6. f3 d6 7. e4 Nbd7 8. Bd3 e5 9. Ne2 c5

10. d5 Waiting for my opponent to play c7–c5 is essential. If I had not waited, my opponent would have the resource of Nc5.

10…Kh8 11. O-O Ng8 12. f4 Qe7

13. f5 My opponent has played very passively, allowing me to have a significant space advantage.

13…Ndf6 14. Ng3 Bd7

15. Bg5! This key idea is called a provocation. The idea is to provoke my opponent to play h7–h6, creating a weakness in front of the king.

15…h6 16. Be3 Nh7 17. Qd2 Qh4

18. Nh1! The best idea from me in the game. My goal is to attack h6 so I will rook lift, and maneuver my knight to f2 and then g4.

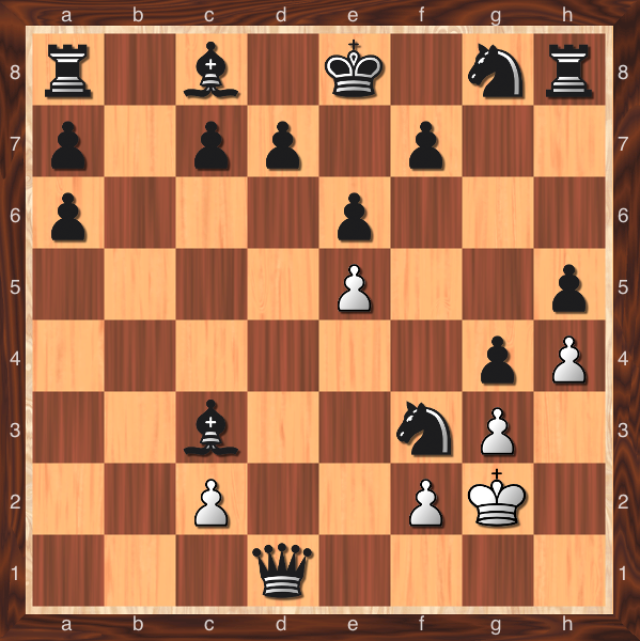

Qe7 19. Rf3 Nhf6 20. Nf2 Rfb8 21. Rh3 Qf8

22. g4 A dream position for me. I will attack the h6 pawn with my g–pawn.

22…Kh7 23. g5 Ne8

24. gxh6 I think I could have waited and played 24. Ng4, but this works well.

24…g6 25. fxg6+ fxg6

26. Rf1 Not even worrying about my rook on h3. I am inviting 26… Bxh3 27. Nxh3 rerouting the knight on g5.

26…Nef6 27. Rf3 Qe7 28. Nh3 Bxh3 29. Rxh3 Rf8 30. Bg5 Qd7 31. Rhf3 Qg4+ 32. Qg2 Qxg2+ 33. Kxg2 Rf7 34. Bxf6 1–0

An easy, but fun win for me. By creating holes in my opponents position, I was able to win a piece. This was a much more thematic and strategic way to attack the weaknesses on the kingside. If you bring over pieces to attack, then your opponent will buckle and crack under pressure. FM Mike Klein once said in a seminar I was in, “If you put pieces near the enemy king, good things will happen.” I think that this mentality is exactly what is needed when attacking weak pawn structures in front of the king.

Feel like I missed something? Feel free to comment!