In spending Thanksgiving here in Pittsburgh, I finally got to sit down and start my preparation for December’s Pan American Intercollegiate Games. This year’s edition of the Championships will be in New Orleans, marking my second trip there this year, having already made the trip south for the US Junior Open this past summer. Last year I managed to hold my own on board 4 in Cleveland, scoring 4.5/6 with no losses throughout the tournament to earn my Candidate Master title, while also producing this tactical gem against a Webster University team:

This year, our team is much stronger, and I know my teammates will be depending on me to perform once again for a strong team finish. I will play again as a fourth board, and I plan on making the most of my second appearance for the University of Pittsburgh.

Speaking of making the most of opportunities, how about the Pitt Panthers defense this past Thanksgiving? Last Saturday, I went to the final Pitt regular season game against Syracuse, in which the two teams for a college football scoring record in a 76-61 Panther win. How does this have to do with chess? Hear me out – Pitt was never in danger of losing the game, consistently up two to three touchdowns throughout the second half. However, the defense lacked the technique to lay the knock out punch to end the game. There was no critical third down stop, late interception, so the Orange kept scoring and forcing Pitt to prove it could stay on top.

Our game is a little more brutal. Fail to put your opponent away, and you leave yourself open to even losing – no matter how much material you are up! So technique is probably one of the most important elements of tournament preparation.

As of last week, I thought I had my mind made up on what I wanted to discuss in today’s post (and trust me, I will at a later time), but last Saturday’s game pushed me to add to my ongoing series, Endgame Essentials, which you can find by searching the title in the search bar.

Endgames, generally speaking, are the toughest phase of the game, and a lack of good technique can make the difference when it comes to converting an advantage. With Saturday’s game in mind, I decided it was time to expand on my Endgame Essentials series.

For today’s post, I’ve selected four recent non-World Championship games to discuss. I chose two positions because I thought the planning behind White’s play in each game was particularly instructive, and really punished Black for poor decision-making. In the latter two, I will discuss “the grip”, a term that was formally introduced to me by chess.com’s death match between Magnus Carlsen and Hikaru Nakamura. I will briefly go over that game, and then share a recent Nigel Short game in which Black tried to break the grip, which ultimately decided her fate.

With the exception of Carlsen’s game, I chose games from the Khanty-Mansiysk Women’s Grand Prix, and the recent Beautiful Minds Krulich Cup, which featured many strong players in a round-robin rapid tournament. Let’s start with the Vallejo Pons’ game from Krulich.

Settling In

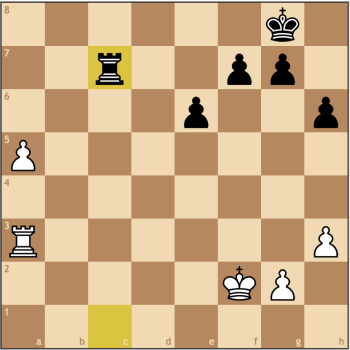

As we can see here, the Spanish GM has a nice lead in development, as well as more logical piece placement. But how does this become enough to win? We have a symmetrical pawn structure, and Black has no weaknesses. It took Paco exactly six seconds to make his next move which I find amazing! After some (brief) consideration, White decided he needed to play for squares and chose 14. f5!. This makes a lot of sense, Black’s pawn on f6 makes it impossible to put a piece on e5, so White points out that e6 can no longer be protected by a Black pawn. This will also make it difficult for Black to find a good square for his c8 bishop, which further highlights the awkwardness that is Black’s position. While White placed his e2 knight on f4, Black was rushing to get his d7 knight to c4. The game followed 14…Nb6 15.Nf4 Nc4+, giving us this position:

Is Black out of the woods? Not yet. While the Black knight seemingly found a good square, it’s life there turns out to be rather short lived. Black meanwhile has problems defending the e6 square, as a visit from the f4 knight is looming ahead. 16. Kc1 is an option I think many players would play without much consideration, but Paco wass able to point out that Black must do something about the impending landing on e6, and found a creative way to change the structure.

Here he chose 16. Bxc4! willingly parting with the bishop pair, because Black must now take on f4. In doing so, all of Black’s active pieces come off the board, leaving White with a technical task. The game continued 16…Bxf4+ 17.Qxf4 Qxf4+ 18.gxf4 dxc4 19.Rhg1 Rg8 20.Ne4!

Now having drawn the Black rook to g8, the knight makes a cermonious entry into the game. Black cannot afford to take on f5 as Black will lose two pawns after 20…Bxf5? 21. Nxf6 Rh8 22. Rxg7 and Black might as well resign. With this tactical justification, we see that White’s structural choice is justified. Black’s pieces are stuck where they are, guarding g7 and f6. Now White’s technique is critical. Should the position up too quickly or Paco were to miscalculte, the bishop on c8 could get out and the game can become much harder to win. In these kinds of positions, it’s easy to get lost in complications, so instead Paco makes the simple decision to heckle Black’s c4 pawn with 20…Ke7 21. Kc3 b5?

Perhaps the “?” is an overstatement considering Black’s task to defend is extremely difficult, but now Black has created a path for White’s king. Black doesn’t have an effective way to control these dark squares, and doesn’t have much counterplay to slow White down, and after 22. Kb4!, the recognition of the game became clinical for Paco. It’s important to note that 21…Bxf5? loses on the spot to 22. Ng3+ since the king is exposed to the e1 rook. White has more than enough targets to win now, and the Spaniard does so with ease. 22… Bd7 23.Kc5 Raf8 24.Ng5+ Kd8 25.Ne6+ saw the conclusion to the game that Paco had planned out over ten moves ago!

With Black having to take on e6, White’s rook will enter Black’s camp for a clean up on aisle six as the c6 pawn drops and the d-pawn becomes a passer. I have a lot of admiration as to how Vallejo Pons played out this game, and his technique made his 2500+ grandmaster opponent look like a patzer! The conversion is relatively simple from here, and if you wish to see it, you can visit the game here.

We’ve got other things to see, so let’s fly over to Khanty-Mansiysk to see how Ukranian Grandmaster Natalia Zhukova found a nice way to put her French counterpart away with good technique.

For those of you who aren’t following the tournament, this particular leg of the Women’s Grand Prix is especially important, as it will select one player to qualify for the Women’s World Championship match.

The position we have here looks like it should peter out to a draw, as again we have a symmetrical pawn structure. How would you react if I told you Black lost in just 12 moves? Of course its hard to fault Skripchenko as she was in serious time trouble, and when the game ended, she had less than a minute with seven moves left before the next time control. Nonetheless, Zhukova made practical decisions while also pushing her opponent to the edge. Here she started with 23. a4!, in my opinion, the only way to play for an edge.

This idea of creating a potential passed pawn is an idea I’ve discussed numerous times on Chess^Summit. Here Black realizes that she cannot push the a-pawn since Qe4-a8+ would see it fall to a simple fork. Recognizing this, the pawn on a7 immediately becomes a valuable target – should it drop, White’s a-pawn will roll down the board and promote! Pressed for time, Skripchenko made natural moves, but this idea prevailed and wins the game. 23…f5 24. Qc6 Rc7 25. Qa8+ Kh7 26. Rb8

While a7 might be Black’s only structural weakness, now Zhukova has strong control over the eigth rank, which will help draw out the Black king. As I covered in my first Endgame Essentials, king safety is extremely important in endgames, and that will turn out to hold true here too. Black toggled around for the next few moves before bailing out with a queen trade, but the damage has already been done. 26…Qf7 27.h4 Kg6 28.a5 Qd7 29.Rd8 Qc6+ 30.Qxc6 Rxc6

The a7 pawn will drop, but Skripchenko had …Rc6-a6 and …Bd6-b4 planned to get the a-pawn back and draw. But Zhukova saw farther. Can you see what she saw? I gave you a hint earlier if you’ve been reading closely, when you think you have it, check out the rest of the game here and see if you calculated like a Grandmaster!

The Grip

Now time to discuss the “real lesson” for today’s Endgame Essentials lesson. As I mentioned before, I first heard of this as a term from chess.com’s Death Match, so I figured I’d share that moment here (Youtube won’t let me truncate the video, the game ends about 5 minutes in):

As you can see, the grip offers a slight advantage when handled correctly – you could even see GM Robert Hess’ opinion of the position change as it became more apparent that only White could play for a win. Now that you’ve seen the grip used by the world’s best, let’s see it in action in Krulich as former World Championship challenger Nigel Short uses it to take down former Women’s World Champion Mariya Muzychuk.

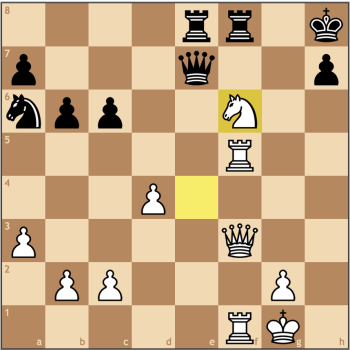

Before we get too carried away, I should start by saying that Black was vastly out prepared in this line. The former World Champion chose 12…Qb6?! to attack f2, but after some calculation, we realize that …Ng4xf2 is not possible because White will play Nc3-a4 and the knight on f2 will fall before it can win the exchange. With this tactical failure, it’s not too difficult to see that soon Black’s d6 pawn will just fall and White will be simply better.

However, it’s technique that we care about today and Short was able to use the grip to crush Black’s position. He started with 13. f3 Ne5 14. Qxd6 Qe3+ 15. Qd2 Qxd2+ 16. Rxd2

It’s already not too hard to see where this game is going, White is planning to advance his kingside pawns and create a grip. Black must decide how she intends to counter – develop or stop White’s plan, both of which seem rather grim. Muzychuk opts for 16…b6?!, letting White create the grip. After 17. f4 Ng6 18. e5 Be7 19. g3 Bb7 20. Bg2, we arrived at this position.

Here we see that Black’s decision to finachetto her light squared bishop may have been a mistake, as now they are coming off the board, and White managed to get a grip with minimal counterplay from Black. Hard to criticize Muzychuk though, she was already in a worse position, and its not exactly natural to continue putting off development in such a position, especially in rapid time controls.

Realizing that h2-h4-h5 is coming to harrass the Black knight on g6, Muzychuk took her chances and tried to break open the grip. In doing so, she creates a new set of problems. 20…Bxg2 21. Rxg2 f6 22. exf6 gxf6 23. Re1

We can talk about pawn islands now, right? An elementary concept, but an important one nonetheless – in breaking the grip, Black has new targets on e6 and f6, and its not so clear how the Ukranian intends to hold on. This may have been necessary though, the computer’s choice of claiming the d-file is worse after 21…Rfd8 22. h4 h5 23. Ne4 (see below) and White enjoys flexibility while Black has very little.

This isn’t that hard to calculate, so this means that Muzychuk deliberately chose against, even if at face value it seems easier to play. Black’s knight has no mobility, and if it moves, an idea like g3-g4 with the idea of attacking the king is not inconceivable. Thus is the power of the grip. Our game continued with a cute tactic, 23…Kf7 24.Rhe1 Bb4 25.Rxe6! Ne5 26.Rxf6+ Kxf6 27.Nd5+ Kf7 28.Rxe5

The position has settled down, and in return for the exchange, White now has a significant pawn majority on the kingside and a weak king to attack. Once White plays c2-c4 this knight will become planted in the center and will be worth at least a rook! White won rather simply, just pushing the kingside pawns after winning h7, and Black didn’t really have a chance to equalize. You can check out the last of this game here.

Takeaways

So as you can see, in each of these four games, endgame technique was crucial in getting a win and not giving the opponent any chances.

As I’m sure the Pitt defense will do this week, I’ll be evaluating my own technique to make sure I can put away “won games” in each phase of the game. Tactics and strategy are important, but being able to recognize winning endgames takes practice and great patience. After all, you shouldn’t be allowing the other team to score 61 points in any game anyways!

The so-called “Dirty Wizard”

The so-called “Dirty Wizard” Kostya sticking to his beloved King’s Indian vs. Alexei Shirov (Photo: Mike Klein)

Kostya sticking to his beloved King’s Indian vs. Alexei Shirov (Photo: Mike Klein) With IM Keaton Kiewra in Dublin, trying our 1st (or was it 2nd…maybe 3rd?) pint of Guinness

With IM Keaton Kiewra in Dublin, trying our 1st (or was it 2nd…maybe 3rd?) pint of Guinness The final round–Kostya gets pretty nervous during chess games. (Photo: Mike Klein)

The final round–Kostya gets pretty nervous during chess games. (Photo: Mike Klein)