Introducing myself

Hi, I’m Franklin Chen, and this is my first post for Chess Summit, and I’m pleased to have the opportunity to begin sharing insights into chess understanding and improvement here. I recently (December 2015) finally became a US National Master, at age 45, and still consider myself an improver. (If you are curious about my history, my personal Web site has an interview of me for the Pittsburgh Chess Club.)

Theory, examples, and practice

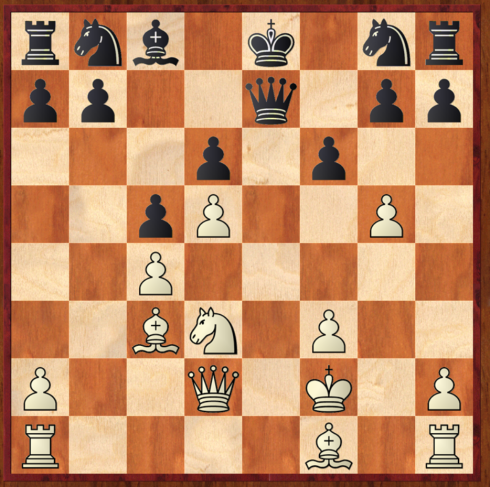

Today I’d like to give an example of how to improve understanding and use of a single important concept, the e5 Pawn break by White against the Benoni Pawn structure, in particular, the Modern Benoni structure:

As you go through my post here, I’d like you to consciously think about how to be effective at chess study. I like to conceptually effective study as being broken into three components:

- Theory: knowing about a concept, in its abstract generality

- Examples: seeing analyzing how the concept works or doesn’t, in specific contexts

- Practice: actually using the concept in your play, and then analyzing whether it worked or didn’t, making note of improvements to make in your play the next time

Theory

The basic theory of middlegames with this Pawn structure is the following:

White has an extra King side Pawn, on e4, and it would like to advance to e5 to attack Black’s d6 Pawn, which is very vulnerable because it is the base of a Pawn chain that has no possible Pawn to protect it. If White’s Pawn can get to e5, then it shuts down Black’s Bishop developed on g6, and also might advance to e6, or might support a Pawn or piece getting to f6. White might also advance g4, g5, h4, h5 for a full-blown King side attack on Black’s King.

Black has an extra Queen side Pawn, on c5, and therefore has chances to play against White’s Queen side by advancing with, …a6, …b5, then maybe …c4, …b4. Black’s Bishop on g7 will aid in the attack on the Queen side and also sometimes go to d4 or e5 to attack White’s King. Black has a half-open e-file and can put pressure on White’s e4 Pawn and try to prevent e5.

All very abstract, but it’s useful to know what the possibilities are up front, before diving into concrete examples. Note that when looking at examples, it is critical to examine good and bad play by both sides, not just one side; this way, we avoid the trap of overoptimistic, wishful thinking believing that the side we play has it easy. The beauty and challenge of chess is that most reasonable positions are not winning or lost but contain resources for both sides in case one side plays inaccurately (and in human chess, that always happens eventually).

Example from Isaac on how not to play against him as White

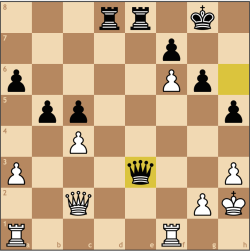

Last month, Isaac analyzed one of his games in which he was Black in this Pawn structure and his opponent as White misplayed the middlegame and allowed Black easy play on the Queen side, resulting in this won position:

White is completely lost here, because Black’s Queen, Rook, and Bishop have broken through: White had not even made any progress in the center or King side, but instead mistakenly not only helped Black open the b-file, but also went after winning Black’s a6 Pawn rather than protecting the critical b2 Pawn from capture.

Remember this position! At the end of this article, you’ll understand why.

Examples of Mikhail Tal losing horribly as Black!

Now that we’ve seen White punished for imprecise play, let’s see examples of Black being punished. I really like the following examples, in which the great attacking legend Mikhail Tal, who played the Modern Benoni as Black a lot and won many brilliant games as Black, actually got completely crushed by not being careful about White’s own attacking resources involving the e5 Pawn break!

Penrose-Tal, 1960

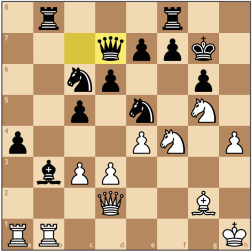

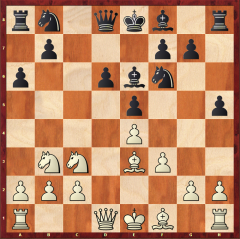

Penrose-Tal, 1960 reached this position, which White to move:

White looks in trouble

Let’s face it, the position is looking really bad for White here. It’s looking like Black will be playing …b4 next move, pushing White back. Meanwhile, White doesn’t look like he can get in e5 any time soon, given that White’s only guarding the e5 square with the f4 Pawn, while Black has the d6 Pawn, Knight, Queen, Rook, and Bishop all majorly overprotecting the e5 square.

Let’s say White tries to blunt Black’s Bishop and get more control over the e5 square with 19 Bd4. But then 19…Bxd4 20 Qxd4 b4 21 Nd1 Ba6, and White clearly stands worse, with no hope of pushing through with e5 or anything else on the King side, while Black is swarming in on the Queen side:

White had something ready

So you might think, there goes another dominating game by Tal as Black. But he was in for a big shock: White played 19 e5 here!

Yes, it loses a Pawn, as we already observed, but the critical insight here is that e5 can, in the right circumstances, be powerful even if it is a Pawn sacrifice. Let’s see why: after 19…dxe5, 20 f5! is the key idea, reaching this position, which is in fact winning for White:

Black to move faces many difficulties. Make note of the following transformations in the game after just two moves:

- Black’s Knight on c5 is no longer overprotected, since the d6 Pawn has been deflected to e5.

- Black’s Bishop on g7, which had so many threats against White’s Queen side, is now blocked up.

- White’s Pawn on f5 threatens to take on g6 and open up the f-file for White’s Queen and Rook.

- White’s Bishop on d3 is now unblocked against Black’s King side.

- White’s Knight on c3 now can hop to the cleared e4 square to attack Black’s King side.

You can study the full game (linked above) for details, but let’s just say that after reaching this position, White played 26 Nc5 winning Black’s Knight on d7 and the rest was just a matter of technique:

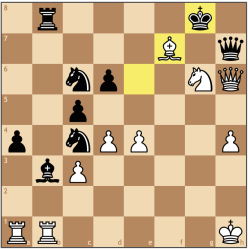

Korchnoi-Tal, 1962

You’d think the great Tal would have “learned” to watch out for the e5 sacrifice idea and wouldn’t fall for it again, but oops, he did it again! We’re all human.

In this position, Tal as Black has just played 18…b5, frantically trying to get in Queen side counterplay. But 19 e5! followed. Let’s look at the positional transformation in this example after 19…dxe5 20 Nde4.

Now that you’ve seen the previous example, you might want to think for yourself and write down a list of what has changed, before reading further to check your answers. I’ve found that it’s really important to try to work out your thoughts, and even actually write down, as though making a commitment to your beliefs as though you were really playing, before checking answers, rather than just passively reading:

OK, here’s a list of transformations:

- As in the previous game, White has forced Black to self-block the e5 square, which is no longer available for Black’s Knight, Bishop, or Queen.

- As in the previous game, Black is now suddenly weak rather then overprotected at c5.

- White has an immediate threat of d6. Note that in the previous game, this motif was not present.

- Even Black’s b5 Pawn is now vulnerable, because it was never overprotected in the first place, and now if Black’s Knight on c7 gets chased away, it will fall.

- Interestingly, unlike the previous game, where White basically dominated the King side, here, White is suddenly operating on the center and Queen side.

Note how each concrete situation will have its own list of possible transformations. That’s why it’s important to study many examples of the theme of the e5 sacrifice, and when encountering the possibility in your own games, to check whether it actually works. Note that the list here is smaller than the previous list, for example; correspondingly, White’s advantage is not as decisive as in the previous game. But still, after 20…Qd8 21 Nxf6+ Nxf6 22 d6 Ne6 23 fxe5 b4 24 Nd5 Nxd5 25 Qxd5 Bb7, White had regained the Pawn with a large advantage:

The final position before Tal resigned is very entertaining:

Revisiting Isaac’s game

Armed with the knowledge and examples we have seen, let’s go back to Isaac’s game. The whole impetus for my writing this article was noticing something in this position in his game, with White to move:

White played the planless 15 Qg3 here. But when seeing this position, I immediately thought, is now the time to play the thematic 15 e5 sacrifice? First of all, does Black even have to take? And if Black takes, then what are the possible transformations of features of the position? You may want to stop and work out some possible lines.

A note on chess engines

Warning: this position is actually much more complex than the examples from earlier. In fact, after doing this exercise, you may want to check whether your favorite chess engine wants to play 15 e5. Mine did not. My engine did not believe that 15 e5 was as strong as I believed it to be. So this is a reminder that engines are not a replacement for human concepts and intuition: Kramnik famously lost a game against Leko in the 2004 World Championship because he relied on engine analysis that was not deep enough at the time. When studying chess with an engine, use your own knowledge of ideas to generate and check candidate moves and plans with the engine.

What if Black doesn’t take?

Note that Black can simply choose not to take the Pawn on e5, in order to prevent White from advancing with f5. After all, Black could protect the d6 Pawn with …Ne8 or …Qe7, or even not protect the Pawn at all, since if White ever takes, Black could retreat with …Ne8 and try to regain the Pawn, with a blockade of White’s d6 Pawn, and might be able to defend.

The thing to realize here is that White’s e5 advance is not intended for a quick knockout win. It is a positional move that just happens to possibly be a sacrifice. What the e5 Pawn does, if untouched, is restrict Black’s counterplay, so that White can continue to improve his position before making a committal capture of some kind to break through. Note that White’s Rooks are not yet developed. Imagine if they were on d1 and e1 behind the d5 and e5 Pawns. A sample line where Black just ignores the e5 Pawn might be 15…Qe7 16 Rad1 Ne8 17 Ne4 Rb8 18 Qf2 b5 19 axb5 axb5 20 g4 c4 21 Bb1 Ra8 22 g5 and White has made progress on the King side while Black has only been able to advance the Queen side Pawns and move the Rook around:

After Black accepts the sacrifice

Black to move:

This is a fascinating position because White has no direct threats at all and it’s even Black’s turn. Try running an engine on this position. It has to think longer and longer before believing White will eventually achieve a substantial advantage. Here are some features of the position:

- Black’s activity is very restricted.

- White will put a Knight on e4 and advance the Pawn to d6 eventually, supported by a Rook on d1.

- White g4 and g5 stuff might happen, and/or something on f6.

- Black has to watch the c5 Pawn, which is no longer overprotected because the d6 Pawn was deflected away.

- White’s Queen on f3 could be a threat against Black’s Pawn on b7. White is playing on all sides of the board here.

A sample continuation: 16…Ne8 17 Ne4 Rc8 18 d6 c4 19 Bc2 Nef6 20 Rad1 b5 21 axb5 axb5 22 Nxf6 Bxf6 23 Qd5. White still has a bind and is going to finally regain the sacrificed Pawn:

I have not analyzed every possible continuation with the engine, but I have complete faith that White’s advantage must be considerable in every line after the e5 sacrifice. I would welcome any attempt to prove me wrong! In any case, from a practical point of view, without perfect Black play, at least we should be able to agree that White has more than enough compensation for the Pawn.

A game of mine where I faltered

In 2006 (when I was less knowledgeable and strong than I am now), I played a game as Black in which I got crushed by a National Master. I like to think I learned something from that game. Here is an important position, with Black to move:

I should have stopped to think about the features of the position, which is completely fine for Black, but I got complacent. There were too many choices: …b5 looked good, and so did …f5.

I could even play …Bxc3, removing the defender of the e4 Pawn, then go after it. I ruled that out because 17…Bxc6 18 bxc3 Nf6 19 Bf3 and it looks like Black is in bad shape. I didn’t see the tactic 19…Nxe4 which equalizes because of 20 Bxe4 Re8:

Instead I played …Re8 and then White played the “obvious” 18 e5.

I was devastated when I saw this, because what was I thinking when playing …Re8? I had forgotten to check whether e5 was good, since it wasn’t anything special in the other variations I had considered. It’s always important to check for important ideas on every single candidate move even if they didn’t work on the candidate moves you already looked at. I felt so bad that I gave up and panicked, took the Pawn, and after the thematic f5, slowly fell apart. I could not see a good continuation if I declined the Pawn. It turns out there was: because White’s e5 Pawn is still pinned, Black has time to play 18…f5! 19 e6 b5! with counterplay. It looks like Black can try to maintain a blockade and defend.

A final example

To reinforce understanding of a concept, it is important to keep reviewing examples, and nowadays, that is easy because of the publishing of played high-level games online. For example, just by following chessbase.com, I saw a nice game by young 21-year-old GM Benjamin Bok posted in an article there in which he showed how to play the Black side of the Modern Benoni.

In the following position, White has just played 18 e4.

Unfortunately, the threat of e5 is transparent and easily parried, with 18…Ng4. White has misplayed the opening, because now e5 is completely controlled by Black, who has the d6 Pawn, two Knights, Bishop, Queen, and Rook all controlling e5! You know that White is never going to get e5 in. Sure enough, some moves later, we have White to move:

White has done nothing but defend, while Black is already creating serious pressure on the Queen side. Look familiar? This should remind you of Isaac’s game. If the b2 Pawn falls, it’s game over. Guess what?

In this position, Black played 31…Nxb2 and the game was effectively over. I recommend looking at the entire game to see how Black finished White off after winning a Pawn and then switched attention to attacking White’s exposed King. GM Bok made it all look easy, against a FIDE 2470 opponent! The Modern Benoni in the hands of an aggressive player still lives!

Conclusion

In this article, I explored examples of thematic White and Black play in Modern Benoni Pawn structure middlegames. I particularly enjoyed spotting the opportunity for an e5 Pawn break in Isaac’s game. I hope we will all watch out for this idea in our games, whether to play it or to defend against it.